During the 19th century, panoptic architecture applied to prisons became gradually widespread in Europe, prisons in which the feeling of being watched by the eye that sees all would implant a sort of censoring chip inside each prisoner. When Barcelona hosted the Universal Exhibition, in 1888, it closed basements and dungeons and also opened its model prison.

It is said that at the beginning it was known as hotel entença (the street name) because it was the first time they saw a prison with individual cells. Finally, the name La Modelo was kept. The center of the watchtower served also as a chapel: Bentham’s eye wore a cassock in these lands.

Going through the sordid corridors of this radial architecture overshadows the thought and one almost forgets that here we came to see art, singular art, of course. Current artists at risk of social exclusion are exposed along with psychopathological and mediumistic drawings from different periods.

Mery Cuesta, curator of this exhibition, “Irreducible Art”, tries to free of so much academic classification and commercial strategy all branches of marginal art, since Dubuffet, in the 40s, gathered, theorized and valued as the only art worthy of this name to what he labeled as Art Brut.

A few decades before the birth of this nomenclature, Paul Klee invited visitors to the first show of “Der Blaue Reiter” (1911) to contemplate the exhibited works thinking about a non-traditional filiation: ethnographic museums, kid’s bedrooms (prior to being “corrupted by education system”) and mental patients.

At the end of the 19th century, some psychiatrists were beginning to investigate the therapeutic potential that creation could have for inmates, but what became a true reference for avant-garde artists was the publication in the 1920s of Hans Prinzhorn’s study Artistry of the mentally ill.

Dubuffet wrote: art does not just lie in bed we made for it; it would sooner run away than say its own name. His thought contradicts his own efforts to make marginal art make marginal art (psychotic, childish, primitive art …) Art par excellence. Depending on how you look at it, Dubuffet efforts can be an absolute nonsense or a fascinating adventure.

Later, American theorists, critics and collectors provided the name Outsider Art, a broader concept that can be divided into countless “tags” prison art, folk art, isolate art … Even, there are many artists who adopt it as a cool nickname.

Mery Cuesta avoids the double danger that faces this type of art, that is, commercial trivialization and romantic mythification. The exhibited works come from collections gathered in different periods and by different types of institutions or individuals: medical collections, foundations of contemporary art (Fundación Bassat), centers that work with people at risk of exclusion, occasional buyers of outsider art, as well as some intervention made in situ.

It is interesting the implicit dialogue between container and content, between the Model with its ghosts and scars (the last graffiti of the prisoners has not yet been erased) and an art that initially also was made in seclusion, born out of the need to cross physical and psychic barriers. Two forces converge, that of some paintings claiming their uniqueness and that of a place that, like all penitentiary institutions, deprived prisoners of individuality.

The exhibition occupies the fourth gallery, distributed among the cells. As a preface, we find photographic documents and records of the Frenopático de Les Corts, along with a floor plan where we see first, second and third class’ rooms. Despite admitting only wealthy patients, this psychiatric center was a pioneer, in the Catalan area, both in internal architecture distribution (each inmate had a room) and in curative treatments. At the end of the 19th century, the “madman” stopped being seen as “incurable beasts”.

The following prison cells are occupied by drawings of the 70s made by patients of Dr. Obiols and Dr. Ramón Sarró (psychiatrists who explored the possibilities of art therapy), such as the “Santboiano” who liked to paint horned chimeras with scaly bodies, or Martin’s anthropomorphic birds, whose seraphic themes, and formal synthesis remind us of Romanesque frescoes (we remember the archetypes that connect us with primordial times in Jungian symbolism).

If in the first cell we seem to hear Jung (the spiritual and eternal inscribed in the symbols), in the second we hear the Freudian mantra of repression and libido, the fights between Self, Super Self and Id, to which the Catholic force of the time is added: “Do you masturbate? Will you go with prostitutes? “Is the inquisitorial interrogation of the Conscious, materialized in shadows and strangling the Unconscious until it screams an agonizing “No “.

We read, in these notebooks, psychopathologies fairly common in all sorts of men although not commonly confessed with such regret: “I fail because I always see women as a sexual object and so much sex is not good” writes Albert. He illustrates his words with a naked woman who, like a femme fatal, tempted him while his parents and the doctor try to restrain his impulses: “the conscious fails you, Albert,” the latter tells him.

More irreverent are the paintings that Pedro Izquierdo made. He was fined for selling books left on the streets, and his response was to cover the fine with colorful paintings: “municipal henchmen” wield their truncheons but he, as a Charon with a long beard, makes fun of them while escaping in a boat and farting. Fantastic houses, stray dogs, swine faces, and his obsessive notes on margins compose other scenes.

Another singular character who also wandered through Barcelona streets and who, like Pedro, disappeared without leaving any trace other than his valuable work, was the Senegalese Housseinou Gassama. He was homeless but he sold his houses by cubic centimeter. He drew them on wooden boards, minimalist and elegant, a Le Corbusier-style, that guy who dreamed of eradicating the begging in the cities.

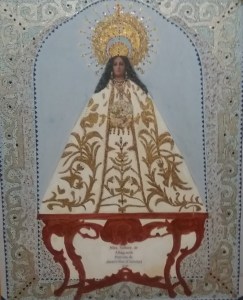

From the homeless to the homely: Julio Julián, with the devotion of an icon painter, made portraits to vedettes of the seventies, bullfighters, virgins … using magazine cutouts, making them glitter lace, making them up. An authentic folkloric iconostasis that surely would have been thrown away if, when he died, some neighbors (he lived in El Prat de Llobregat) would not have rescued them.

In the cell dedicated to the “visionaries”, we find Josefa Tolrà, the medium of Cabrils who amazed the artists of Dau al Set in the ’50s (see the interview with Pilar Bonet).

Necessity, vision, spontaneity, primitive and singular are the epithets that Mery has chosen to avoid the annoying tag “art” of all derivatives of irreducible art.

Gone are days when some aimed at the revulsive power of a self-taught art capable of replacing “high” art. It is not only that the margins are easily phagocytized by the center, but that the “alternative” artists no longer have bohemian secrecy, and that is fine. Miss Cobra, who occupies the last cell, is advertised across all her social networks. The key, maybe, is that everyone should know how to preserve an “irreducible” depth from where something “brut” continues to emerge.

Anna Adell

L’Art Irreductible. Miratges de l’Art Brut

La Model Espai Memorial, Barcelona, until 17th Feb. 2019

Nau Gaudí, Mataró, until 20th January 2019

Organizer ICUB. Coord. Fundación Setba

Curator: Mery Cuesta